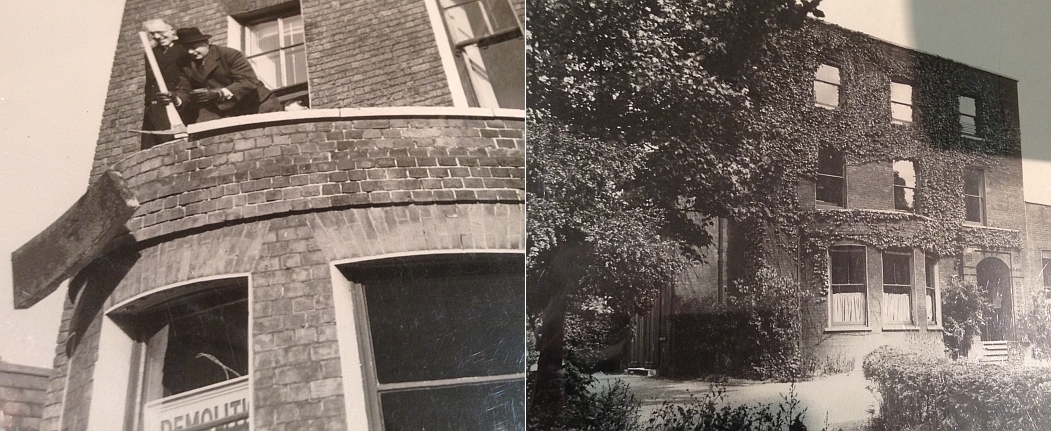

Sir James Marshall (left) and Alderman Basil Monk demolishing the house on the right

Sir James Marshall (left) and Alderman Basil Monk demolishing the house on the right

Why did Croydon turn into a mini-Manhattan?

Historians and sociologists usually tell us that social change is caused by impersonal economic forces and that it is naïve to blame individuals for these changes. But Peter Saunders, a distinguished sociologist, has pointed his finger at one man and said he was responsible for the horror that is modern day Croydon. That man was Sir James Marshall. This claim was made in Saunder's "Urban Politics : A Sociological Interpretation" which was published in 1979.

Saunders went to Selhurst Grammar School and witnessed at first hand the Croydon redevelopment. His book is full of caveats and there is a lot 1970s sociological jargon to wade through but by the time you reach final pages it is clear that Sir James Marshall brought the skyscrapers and the multi-storey car parks to Croydon. Saunder's book started as a student thesis. Between 1971 and 1973 he interviewed Croydon Councillors, Croydon Council Officers and local businessmen. He wanted to know how political power worked in local government. By the time he published his work Saunders was a university lecturer and consequently much of the book is padded out with thoughts about how his findings fitted in with the current sociological theories. Despite this I still found it an interesting read. Sir James Marshall is by far the most important person in the book but I don't think Saunders interviewed him. That's a pity because instead of wasting time teaching ephemeral theories to uninterested students Saunders could have written a book about Sir James Marshall and become the UK's Robert Caro.

Many of the councillors interviewed by Saunders felt that they should not be bound by the wishes of the electorate. They were elected to use their own initiative. These councillors knew that most people had no interest in council politics and the councillors knew they were unlikely to have to account for their decisions. Aldermen like Sir James Marshall were not even elected by the public they were nominated by other councillors. Within this group of unaccountable councillors were a small elite group who decided policy. They didn't think they were accountable to the electorate or even to other councillors. Saunders described how the various committees worked and he explained how being chairman of a committee together with being a member of the policy subcommittee means you can usually get what you want. Saunders was told that once the political elite have made their recommendations "all that usually remains to be done is to ensure that the members fall into line behind their leaders. This they invariably do with little trouble".

Given that the political elite can get what they want without too much concern about making decisions democratically the next question is why would they want to bring the skyscrapers to Croydon. According to Saunders the ruling elite identified the interests of the council with the interests of the business community. For example when questioned about the enormous cost to the council of all the town centre car parks a councillor replied "They are needed for the Whitgift Centre shops and surrounding area". Saunders wrote "The baldness of these statements is indicative of the inability of the council leadership to distinguish between business interest and public interest." The skyscrapers were brought to Croydon because it was good for business. It would mean more money for Croydon businesses and more money for Croydon council via business rates. Nowadays they would say more jobs as well, but in the 1960s Croydon had full employment. If you didn't have a job at that time you were either very sick or very lazy.

It might be wondered why there was so much office development in Croydon compared with other places. That's where Sir James Marshall comes into the picture. He was extremely influential in Croydon. Oliver Marriott, a financial journalist and later a businessman, wrote the following in his 1967 book "The Property Boom" :

What Marshall said, went. Extremely commercially minded and an orthodox Conservative, he was, as it were, the managing director of Croydon. He got things done quickly - and they worked. When I talked to him about the transformation of Croydon, he remarked wryly that "the best committee was a committee of one". A property developer who worked in Croydon recalled that "One didn't get anywhere if Sir James disproved of one".

As the leader of the council and as the Chairman of the Whitgift Foundation, the largest landowner in the town center, Marshall was able to offer developers an unusual and appetizing deal - a very large amount of land right in the middle of a town with good rail links to London. I don't think any other council near London could have made such an offer. I imagine from his point of view it was a good deal to all the main players - the council, the Whitgift Foundation and The Girls Day School Trust who owned a lot of land on the east side of Wellesley Road.

According to Saunders, Marshall sold the lease of the Trinity School land in 1965 to Ravenseft Properties for annual rent of £200,000, plus a share of the profits plus a £1 million lump sum for a new Trinity school to be build in Shirley. Over the years that deal has been very profitable to the Whitgift Foundation and the charity's 2014 accounts show that they had an income of £52 million. They educate 3,000 pupils at three schools and they have over 900 employees.

I don't know what deal The Girls Day School Trust did when they sold the land and moved to Selsdon but they seem to be on the pig's back now. In 2014 the income of The Girls Day School Trust was £274 million. They educate 19,000 pupils at 24 schools and they have 3766 employees.

Everyone benefited except those who preferred Croydon as it was before the changes and that group seemed to consist of most people. It wasn't just the ugly buildings and the extra traffic. Hundreds had lost their homes to make way for new roads. It seems that an Englishman's home is his castle until the council decides that the house must give way to a motorist who wants to knock 10 minutes off his journey. Saunders wrote :

...a number of working class families discovered in 1965 that their homes lay in the path of a proposed flyover, and with the help of local Labour Councillors organised a campaign against the development. Their protest, however, proved totally ineffective due mainly to the fact that the council had taken its decision years earlier, and their homes were subsequently demolished.

Economically Marshall's Croydon makes sense. If you have something, land or goods, that someone else values more than you and is willing to buy it then you should sell it. Both parties win. You can now buy something you value more than the thing you have sold and the buyer has got something he values more than the money. But that is too simple. Who really owned the council land? It wasn't Marshall. Do the people of Croydon value the new Croydon as much as the old Croydon? I don't think so. Would Archbishop John Whitgift have felt happy about his generous donation resulting in so many temples to mammon?

In the early 1970s the Whitgift Foundation tried the same trick again when it tried to sell the Whitgift School site at Haling Park and move the school to Croham Hurst, which was one of the few large green sites left in the area. This land was another donation by Archbishop John Whitgift. This time the Whitgift Foundation did not have Marshall on their side. Although he was now retired from local politics he was quoted in the paper as saying the move was "a stupid idea". He was backed by the local golf club and many of the middle class residents in the area. The move was blocked.

Today in 2016 Croham Hurst is still unspoiled. Unfortunately it is a bit too far from Croydon to be considered as a feature of the borough. Many of the surrounding London boroughs have something pleasant and distinctive in or near their town centres. Richmond has the river and the park. Kingston has its riverside walks. Wimbledon has the Common. Croydon used to have an attractive old school surrounded by fields in the center but now it just has a concrete canyon and some trams.

Wellesley Road

Wellesley Road

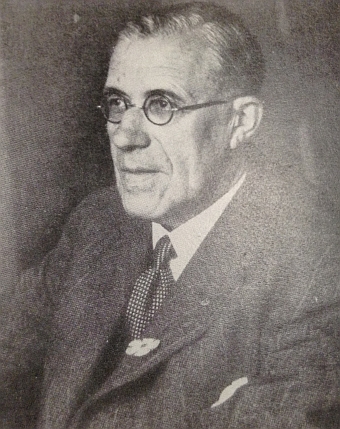

Sir James Marshall 1894 - 1979

Sir James Marshall

Sir James Marshall

Marshall was brought up in Penge. His father was a newsagent and tobacconist. In the 1911 census Marshall was described as a newspaper journalist. In 1928 he was elected as a Croydon Councillor. Marshall's occupation was "a stamp broker". He married Jane Kent in 1939. They lived on a large farm at Woldingham which is about 7 miles south of Croydon. He was knighted in 1953 for "political and public services in Croydon". In the 1970s he moved to Purley and then in 1979 he died in a nursing home in South Croydon. These are the bare facts about Marshall available on the net, but to my mind these facts don't shed much light on his personality or on how he became so successful.

According to one source Marshall went to America with his brother and bought the Arthur Hind stamp collection. A famous story about Hind is that when he discovered he didn't have the only copy of a particularly valuable stamp he immediately contacted the owner of the only other copy, bought it and then tore it up in front of the startled previous owner. When Hind died his famous collection was sold in 1933 at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York but Marshall is not mentioned as one of the buyers in the newspaper report I have read. The collection was sold for $245,000 to various buyers. There was a suggestion in the report that there other parts of the collection. Perhaps Marshall bought something when they were sold.

Whatever the source of the money he must have done well because in 1939 he was living on a 200 acre farm at Woldingham. There were no ugly skyscrapers to block the attractive views there. The main Conservative Party elite insiders in Croydon in the 1940s and 1950s all seemed to be wealthy men. Alderman Monk, who is shown in the picture top left, was the Managing Director of Trojan - a big factory making motor bikes and other motorised transport. Alderman Gibson was the owner of the biggest building firm in Croydon. You can see that they might have had a motive for wanting more roads and buildings.

Some of the redevelopment around the country in the 1960s was accompanied by blatant corruption. The story of T.Dan Smith and Paulson is well known, but I have never read any suggestions of anything similar in the Croydon redevelopment. Marshall would have had the opportunity to enrich himself, but when he died the amount in his will was quite modest for someone who once owned 200 acres of Surrey farmland. He was well off but he was a long way off being a millionaire.

According to one source Marshall was articled at some point to a Croydon architect. If this is true he must obviously have known about or had an interest in architecture. Yet this stands at odds with the happy look on his face in the picture on the top of the page as he and Alderman Monk smash up an attractive old building. Unless, of course, he was a follower of Le Corbusier. Croydon ended up looking like a tribute to Le Corbusier. Coincidentally, Dame Jane Drew (1911-1996), a very prominent architect, town planner and a follower of Le Corbusier, was a former head girl at Croydon High School for Girls on Wellesley Road. She is responsible with her husband, Maxwell Fry, for modernistic buildings in places like Hatfield, Milton Keynes and Harlow. Anyone who has had the misfortune to have visited those towns will have a good idea about the kind of buildings they designed, but I don't think they can be blamed for anything in Croydon. Like Marshall, they preferred to live in the countryside in a traditional house.

Marshall was a bachelor until he was 46. If he had a family to interest him he would have had a little less interest in politics and less time to build up his power base. By the time he got married he already had Croydon in his pocket. All that was left was to do was to do something with it and I think he was just one of those busy and irritating people who need to be moving and changing things all the time. When you can't find the thing you left on the shelf they tell you that you shouldn't have left it there and is now the garage or, worse, in the bin. These people are always doings things. Marshall was going around Croydon doing the things that he thought needed doing. Croydon was his house and he was tidying up the place by smashing down and chucking out all the stuff he personally didn't like.

Marshall just had too much power. Malcolm Muggeridge, another Croydonian, put it very well when he said this in a TV interview : "I hate power. I think man's existence in so far as he achieves anything is to resist power, to minimise power, to devise systems of society in which power is the least exerted".