Looking north from the park building towards Netherton House

Looking north from the park building towards Netherton House

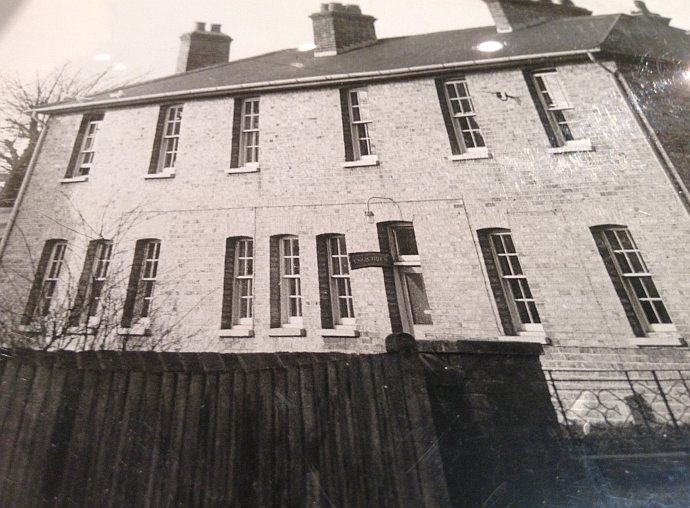

Netherton House

Rear view of Netherton House based on an aerial photo

Rear view of Netherton House based on an aerial photo

Netherton House was renamed Ruskin House after The First World War. The building was mainly used for trade union meetings, Labour Party business and for meetings of various special interest groups. As such it would have played quite an important part in the history of Croydon, but all we have on the net are a few aerial photographs of the building. My picture of Netherton House is a bit unsatisfactory. It is difficult to know what it really looked like, but there are some writings about the house which suggest it was run down and very dusty. Under the control of the Labour Party the building seems to have been neglected and they don't seem to have been too bothered when the council knocked it down. The council showed evenhandedness by also destroying the Conservative Party headquarters across the road in Bedford Park.

The Park Department building

Croydon Park Department building Wellesley Road 1950s

Croydon Park Department building Wellesley Road 1950s

Croydon Park Department building looking towards The Homestead

Croydon Park Department building looking towards The Homestead

Before it was taken over by the parks department this building was probably used by the domestic staff at Wellesley House. The 1871 census shows that is was occupied by Thomas Black, a gardener, and his wife Mary.

Netherton House stables and coach-house.

The building between Netherton House and the Park Department building became the Croydon Repertory Theatre in the 1930s. I was unable to find any photos of it. That surprised me. You would think Croydon would be proud of have a repertory theatre which trained an actor as eminent as Paul Schofield. But it seems that in Croydon the people, like the buildings, are soon forgotten. John Le Mesurier and Richard Wattis are two of the many actors who received their early experience in this theatre. The theatre can be seen on the far left in the following photo extending out of the back of the building between Netherton House and the Park department.

Wellesley Road from Britain from above

Wellesley Road from Britain from above

The theatre was damaged by a bomb during the war and it did not reopen. It became a furniture warehouse. In the 19th century and early 20th century the coachman to Netherton House lived with his family in the rooms over the stables.

View from the corner of Poplar Walk and Wellesley Road before the 1960s redevelopments

View from the corner of Poplar Walk and Wellesley Road before the 1960s redevelopments

2016 view from the corner of Poplar Walk and Wellesley Road

2016 view from the corner of Poplar Walk and Wellesley Road

James Turner

James Turner, a wine merchant, lived in Netherton House for more than fifty years. His main claim to fame, in my eyes at least, is that he was one of the founders of the Football Association.

James Turner (1839 - 1922)

James Turner (1839 - 1922)

James Turner was born in George Street, Croydon. His father, Thomas, was a veterinary surgeon. The 1851 census shows that James and his brother William were attending Streatham Academy as boarders. In 1861 he was living at home with his mother in London Road, Croydon. Although his mother was a widow by this time they were still comfortable enough off to have a footman on the domestic staff. James was described in the census as a clerk to a wine merchant. He was a keen sportsman and he played for the original Crystal Palace team. In 1863 he was a member of the small group who formed the Football Association and who set out the rules for the game. In most histories of the Football Association James Turner has been overlooked. His story is well told here :

Croydon man was the forgotten founding father of the FABy 1871 he had become a wine merchant and he was living in Netherton House. There were four domestic staff living in the house with six members of the Turner family. The 1881 census shows the size of his family had increased to nine including himself and there were eight domestic staff including a butler. At first glance the house doesn't seem big enough for seventeen people to live there, but it had a very large attic. When the Labour Party took over the place all the bedroom partitions in the attic were knocked down to make one or two large meeting rooms. There would also have been at least six bedrooms on the first floor for the family. In 1901 when he was 61 and still working as a wine merchant he was living with his wife and four adult children. They had six domestic staff. Even in 1911 when he was just living in Netherton House with his son they had five domestic staff.

Ruskin House

James Turner moved to a smaller house in Addiscombe and in 1919 The Labour Party bought the building after raising the money via a public subscription. They renamed the house "Ruskin House". I dread to think what Ruskin would have made of the new Croydon. "When we build, let us think we build for ever" he wrote in The Seven Lamps of Architecture. The new buildings in Croydon seem to last two or three decades at most and when you look at them you think even that is too long.

The first president of Ruskin House was Henry Muggeridge, Malcolm Muggeridge's father. Muggeridge wrote scathingly about the habitués of Ruskin House in his autobiography "The Green Stick". The people he noticed at Ruskin House were "teachers, Quakers and ladies of private means forcibly fed in suffragette days" but not many workers. His father, a Labour councillor in Croydon, was trying to become an MP and that gave Malcolm Muggeridge the opportunity to meet famous Labour politicians like Ramsey McDonald and Philip Snowdon. He was not impressed. He found them condescending. His wife's aunt Beatrice Webb, who together with her husband Sidney were Labour Party royalty, wrote that Malcolm Muggeridge's father was "a Fabian and a very worth person, though of modest means". Malcolm Muggeridge commented "Truly, there is no snobbishness like that of professing equalitarians".

Miss Helen Corke

It was fascinating to read in Muggeridge's autobiography about his TV interview in 1968 with Miss Helen Corke, his first primary school teacher. They were complete opposites. Muggeridge was a man who seemed to be born world weary and cynical. Helen Corke believed in progress and human perfectibility. The interview was about DH Lawrence who had been a friend of Helen Corke when they had both been teachers in Croydon 60 years earlier. In 1965 she had written "DH Lawrence: The Croydon Years".At the time of the interview Helen Corke was 86 and Muggeridge was 65. Muggeridge wrote:

I still felt as I had all those years before, that I was in the presence of my teacher, whose rebukes at all cost must be avoided, and whose praise was infinitely desirable. When the cameras had gone, and as the evening wore on, a difference of view, if not a dispute, arose between us. This concerned what human life is about, and where we who are involved so mysteriously in this experience of living are being led. Miss Corke still took the view that mankind have their destiny in their hands, and are passing on to new heights of understanding and achievement, with the prospect of ultimately being themselves masters of their own universe.That was written in 1972. Muggeridge was summing up his, according to him, wasted life. But Miss Corke was still going strong and she was working on her autobiography which came out in 1975. She died in 1978.